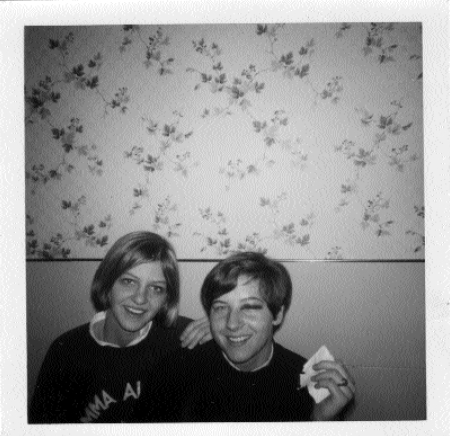

—Syracuse, New York 1967

In 1963, I entered high school. I’d stopped fist-fighting, stopped hating girls, stopped beating up on my brother and calling him a sissy. I now had a best friend, Bonnie McHale, who was, like me, an outlier and an athlete. We’d been blood sisters since sixth grade.

Bonnie lived a mile away from me, and every day after school we’d meet up for softball, basketball, tennis, ice skating—whatever sport was in season. She was better than me in archery, ice skating, basketball, and the back stroke, but it was my job to keep her from thinking so. Actually she was superior in all sports, but I had the psychological edge—I could get to her.

I prided myself on being a leader and joined every group in sight so I could rise to the top. I needed the spotlight. It was my way of proving that I was a good person, haunted as I was by the dark shadow lurking within. Bonnie’s insecurity had other sources, but we were equally besieged and had a need to stand out in the crowd. Her family put her down for not being smart enough, for being so tall (almost six feet), for having strange toes and thumbs, for ears that stuck out. They were merciless.

We both hated ourselves in different ways. I was beginning to be attracted to girls and knew this was an abomination, so I tried everything to compensate for what felt like a fatal flaw. I went to daily Mass, joined the Legion of Mary, performed charitable works every week, read the Imitation of Christ and My Daily Bread, but I was in an impossible predicament.

On one level, I knew myself as a child of God. I was a good person—kind, fair, fun to be around. I didn’t doubt that. But I also carried the weight of being predisposed to evil. Even though I was headed for the convent in a few years, according to everything I’d learned from the catechism and the pamphlets we read in religion class, I was guilty of the worst crime ever. I hadn’t committed any homosexual acts yet, but I knew I was one, which caused me constant turmoil. Inside me dwelt a mystic and a misfit who were always at war. I was rarely free of it and the battle manifested outwardly in terrible ways. One was a betrayal of my best friend.

Despite our competitiveness, Bonnie and I were as close as two girls could be, until one fateful day when she put her arm around me in a way that made me feel uncomfortable. I thought for a second she might be homosexual. That triggered in me a series of actions that are nearly inexplicable.

I didn’t ask her anything about the incident. I never said how it made me feel. I simply leapt to the conclusion that if she was queer, something had to be done about it. My own self-hatred was about to turn outward. Here it was. My first crusade. My own personal Inquisition.

Behind her back, I organized a secret gathering of our friends. I confided my suspicions to the group and whipped up a frenzy of emotion. Then, with the most fervent righteousness, we shunned her. Not one person spoke to her. When she came close, we simply turned our backs or walked away. This went on for days. Then I wrote her a two-page letter and delivered it on the last day of school, right before I went away for two weeks.

I couldn’t have done anything worse to a good friend. I couldn’t have been meaner if I tried to be. I left town and there was no one there for her. None of the other girls called or came around. She read the letter in her back yard, leaning against the peeling red wood of their two-car garage. Over and over, she took in the stinging sentences, trying to make sense of this terrible paradox. I had been her best friend. What had she done? Why had I turned everyone against her? What should she do now? She sat on the ground crying for over and hour. Weeping, grieving, despairing.

She hid the letter in an old tin box in her closet and prayed no one would find it. She read it a hundred times, wondering why? What was I talking about? How could I do this to her? She didn’t even understand some of the words I used, they were so remote and unfamiliar.

When I finally came home, she wanted to talk with me, but I refused. I was cold. Distant. Mean.

“We’re not discussing this,” I said. “I don’t want to talk about it.”

That was the edge I had.

That whole sorrowful disaster had nothing to do with Bonnie. She never tried to be affectionate. She didn’t have a homosexual bone in her body. I was the one who was queer. I was the one falling in love with girls, ashamed of myself but unable to help it. I was the one who had internalized every message I received about the perversity of homosexuals and grown to hate myself. That’s why I tried to make everyone think I was so outstanding—star student, president of the Glee Club, president of Charity Guild Sorority, editor of school paper, yearbook committee. Textbook. A classic case of projection.

Last month, 50 years after the incident, Bonnie and I sat in my living room trying to understand how such a thing could happen between two teenage girls who truly loved each other.

Lines from that letter are still in Bonnie’s head, seared in her memory forever:

“Dear Bonnie,

I’m sorry I have to tell you this…We’ve had discussions about you and your behavior…We think you are queer, a homo…We don’t want you to be part of our circle anymore…You’re not one of us…We can’t be friends…”

Neither Bonnie nor I could recall how the upset was reconciled. Weeks passed, seasons changed, and there we were, pitcher and shortstop, forward and guard, alto and soprano, right back in our favorite positions again as if nothing had happened. We finished high school, traveled through Europe together, found her husband together—she a heterosexual hippie and me and my partner beside her, gay as can be. Once she became CEO of Time Life Warner in Sydney, Australia, she even sent me a round trip ticket so she could tromp me on the golf course of her country club. Still competing, as always, though I no longer have to have a psychological upper hand.

I shared the story with my friend Barbara, a psychoanalyst who’s had a therapeutic practice for 40 years, hoping for an insider’s insight into my actions.

“How ironic that I spent so much energy to combat in Bonnie the very thing I was suppressing in my life,” I said. “I hated myself for being gay, so I projected the whole ugly mess onto her. I tried to make it her problem.”

Barbara reminded me of our body’s remarkable ability to protect us from what we’re frightened about.

“Everything you learned about being gay was interpreted as a threat to your health. And it was, potentially,” she said. “So that denial and projection, that cruelty, was all in the service of defending your self-system.”

My self-system was under attack from every direction—church, society, peers, parents. I did know it wasn’t safe to be that way, but luckily, I can say now and I do, frequently in my prayers, that I’m grateful for being gay, and for more reasons than one.

Had I not been born gay, predisposed to being an outcast, I could not have felt its burden, would not have felt the empathy for others enduring similar kinds of judgment that I now feel in the company of those who are discriminated against.

Had I not been born gay, I would not have developed skills in transcending self-hatred or hatred from others. I would not have had to work on loving myself, enter the dark forest of despair, feel my way into a self love that is extravagant, overflowing, that can be felt by others.

Had I not been born gay, I would not have learned to advocate for change, speak out for justice. I might not have become a social activist, might not understand the workings of other ideologies besides homophobia—racism, sexism, capitalism, patriarchy—and see how they rely on each other for their own self-preservation.

I might never have learned to think originally if it hadn’t been a requirement of my own survival—to banish ideas of anyone’s infallibility, any church’s authority over my life, so I could proclaim my own sanctity on my own terms.

Had I not been born gay, I might have missed the signs to the path of the heart, following the masses unwittingly into consumerism and consumption; had I not been at the deathbeds of brothers with AIDS, witnessed the violence against gays in more countries than my own, watched the transgendering process in my own family, been sent home from the convent because of my queerness, then my heart would not have broken in half, would not have opened itself to Love Supreme, would not have been tenderized by life’s bitter pounding.

I would not have understood disempowered, debilitated, dismisssed in the ways that I do, through the pores of my flesh, the chambers of my heart, the elegant cells of my cerebral cortex. Life wouldn’t have washed over me like a tsunami and I might not know the feeling for the word survivor as I know it now.

I have confessed my sins to Bonnie McHale. I have knelt at her feet and said, “I’m sorry.” I have forgiven myself as she has forgiven me. And that’s all we can do when we make mistakes—mine them for meaning, see how they happened to prod us forward, confess and admit, then continue on resolute as can be. Every tragic incident we participate in has lessons for everyone who shows up at the dance.

As human beings, we can only learn from our human errors.

Bonnie and me, after getting a black eye in a basketball game.